//The best thing is to realize that you are who you are and you gotta work with what you got.//

Zendaya’s stars in the upcoming Spider-Man: Far From Home film as Michelle “MJ” Jones, who is presumably being set up as a love interest for the young protagonist. But despite her already long career in the business, Zendaya was surprised to land the role in Homecoming, mostly because she assumed she’d have to campaign to play MJ as an actress of color.

Zendaya seems to understand the pressure and iconography around comic book properties, as well as the potentially toxic fandom. Mary Jane Watson is typically portrayed a red-headed caucasian girl– and one far perkier than Zendaya’s Michelle ended up being. But luckily for her, Spider-Man: Homecoming was already planning on a diverse cast, and therefore a more accurate portrayal of New York City’s melting pot.

When she was 18, Zendaya Coleman graced the Oscars’ red carpet 2015, she glowed. And one of the most regal aspects was her hair — cascading brown locks that skimmed her lower back and framed her face. She was stunning, and people gushed. I was hit with the same sense of triumph I felt when actress Viola Davis walked the Oscars’ red carpet in 2012 sans wig and with her natural short coils.

Giuliana Rancic of E!’s Fashion Police was an exception. She said of Coleman’s locks, “I feel like she smells like patchouli oil … or weed.”

Coleman issued a statement saying Rancic’s comments were “not only a large stereotype but outrageously offensive.”

Though the show is known for over-the-top commentary, Rancic realized she crossed the line, apologizing to Coleman via tweet. She said her comments were “referring to a bohemian chic look” and had “NOTHING to do with race…”

She’s wrong.

Locks are an unapologetically black hairstyle, from their origins to the growing process.

And while natural black hair has been put down for hundreds of years in the United States, Coleman was showcasing pride.

This is no “bohemian chic look.” Locks are symbolic of a culture. They are strength. They are power. This is a style that has grown with black people, changing form and meaning depending on which continent the people of the diaspora lands.

My father is well-versed in Rasta culture, and growing up I learned that dreadlocks are rooted in a strong sense of black pride and spirituality. Rastas wear their hair dreaded to make a statement, uproot the status quo, embrace who they are, and not conform to European ideals of beauty and appropriateness.

Considering that Coleman was wearing faux locks, I can’t say she’s a poster child as a natural-hair advocate, but here’s why she’s an effective one:

Zendaya Coleman was a Disney Channel star with a predominantly white, preteen fan base. No one expected her to make statements in defense of black culture. But imagine the conversation those young fans are now having.

Of course, Coleman is not the first to wear locks on the red carpet, and Davis wasn’t the first to wear a low-cut Afro. But the switch made a powerful statement, and the prejudices surfaced as a result.

Rancic would never have made comments about the hair of director Ava DuVernay or singer Ledisi, because they’ve worn their hair that way for years. Consider Rancic’s comment that she preferred Coleman’s previous “little hair” style — a straight bowl cut. It’s as if she said, “If you’re going to do extensions, why THAT?!”

It’s similar to a question Chris Rock often received in his 2009 documentary, Good Hair. In one segment, Rock tries to sell “black hair,” with kinky texture and tight coils, in a beauty supply store. “But this is black hair!” he insists. “For black people!”

The store owners shake their head. Rock asks, “So, my nappy hair isn’t worth anything?”

“No,” they respond firmly.

The “worth” of black hair is a conversation that has expanded from lecture halls and salons to the runway. Coleman was on the world stage rocking faux locks that weren’t small, curled, pinned, or crimped. They were of medium thickness and fairly free. She was fairly free.

Coleman’s choice was a reminder that my natural tresses are good enough for the “fancy” events my mom feels compelled to straighten her hair for, and that our hair has always been elegant.

But not everyone sees it that way. In an interview with the Grio, black actor Anthony Mackie told his nephew not to grow locks, asking, “Do you want to be seen as part of the problem or do you want to be an individual?”

He was playing to the same stereotype as Rancic, one the culture buys into as well.

According to a report by the American Civil Liberties Union, African Americans are almost four times as likely to be arrested for marijuana possession as white people are, despite a similar rate of use. Rancic’s insulting remarks add to the profiling, aligning a hairstyle with drug use.

After a searing backlash, Rancic submitted another apology on E!: “This incident has taught me to be a lot more aware of clichés and stereotypes, how much damage they can do. And that I am responsible, as we all are, to not perpetuate them further.”

Coleman accepted that apology and urged people to acknowledge that “hidden prejudice is often influential in our actions. It’s our job to spot these issues within others and ourselves and destroy them before they become hurtful.”

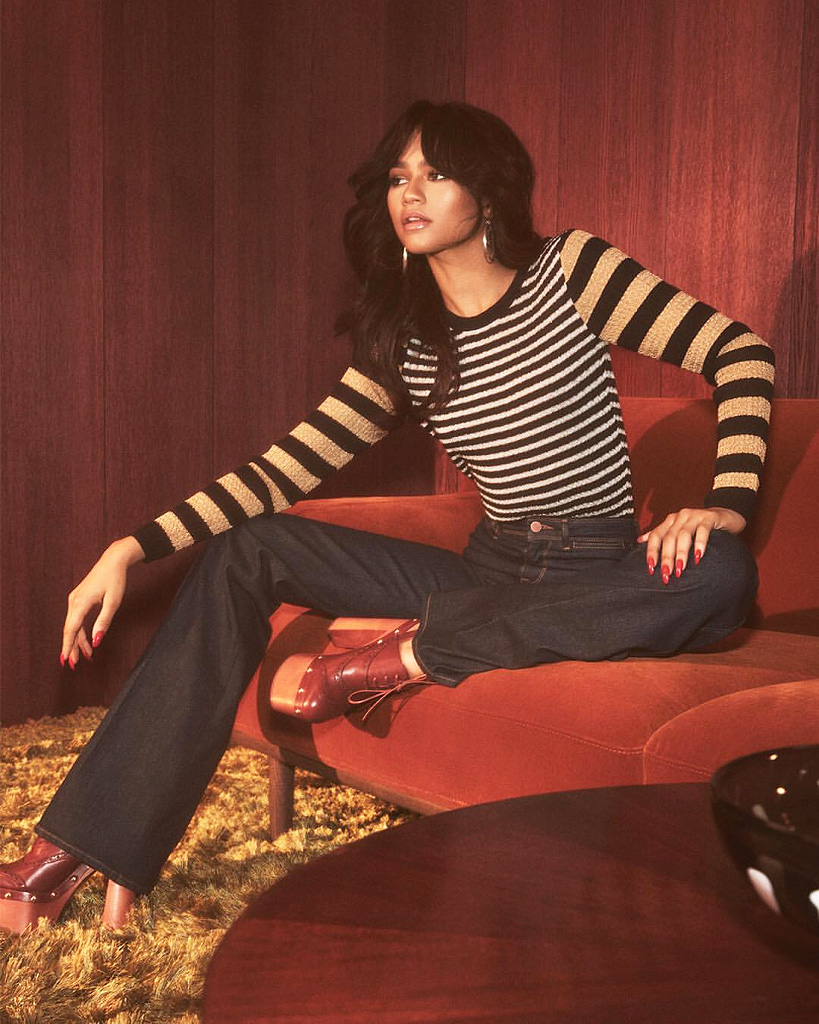

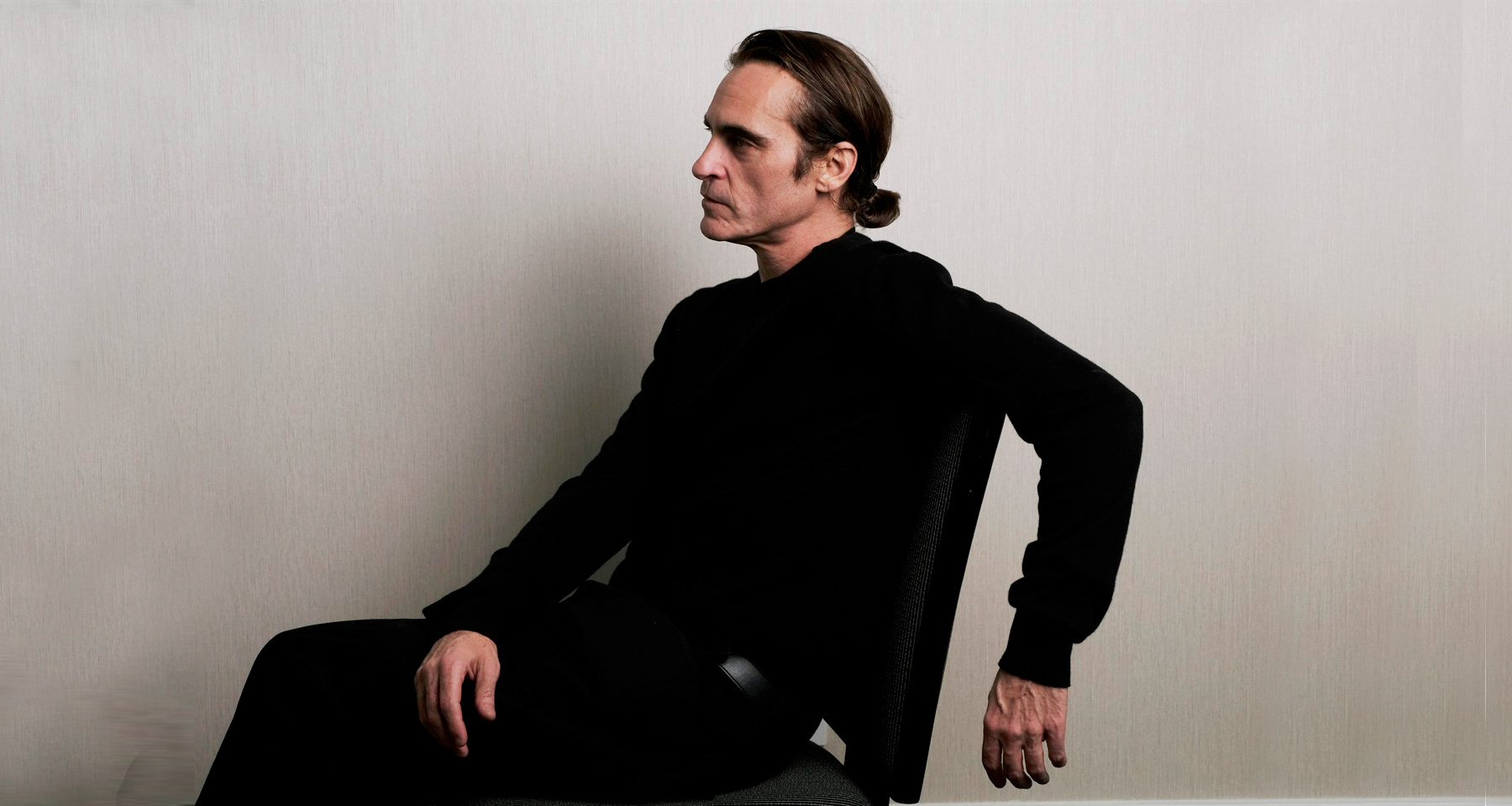

All photographs courtesy of Tommy Hilfiger