ach fall, I try to focus some of my musical attention on an artist and/or album from the popular culture of my lifetime in which I find lessons for my favorite season. In past years I’ve considered the music of Townes Van Zandt, Bob Dylan’s John Wesley Harding, and Wilco’s Yankee Hotel Foxtrot.

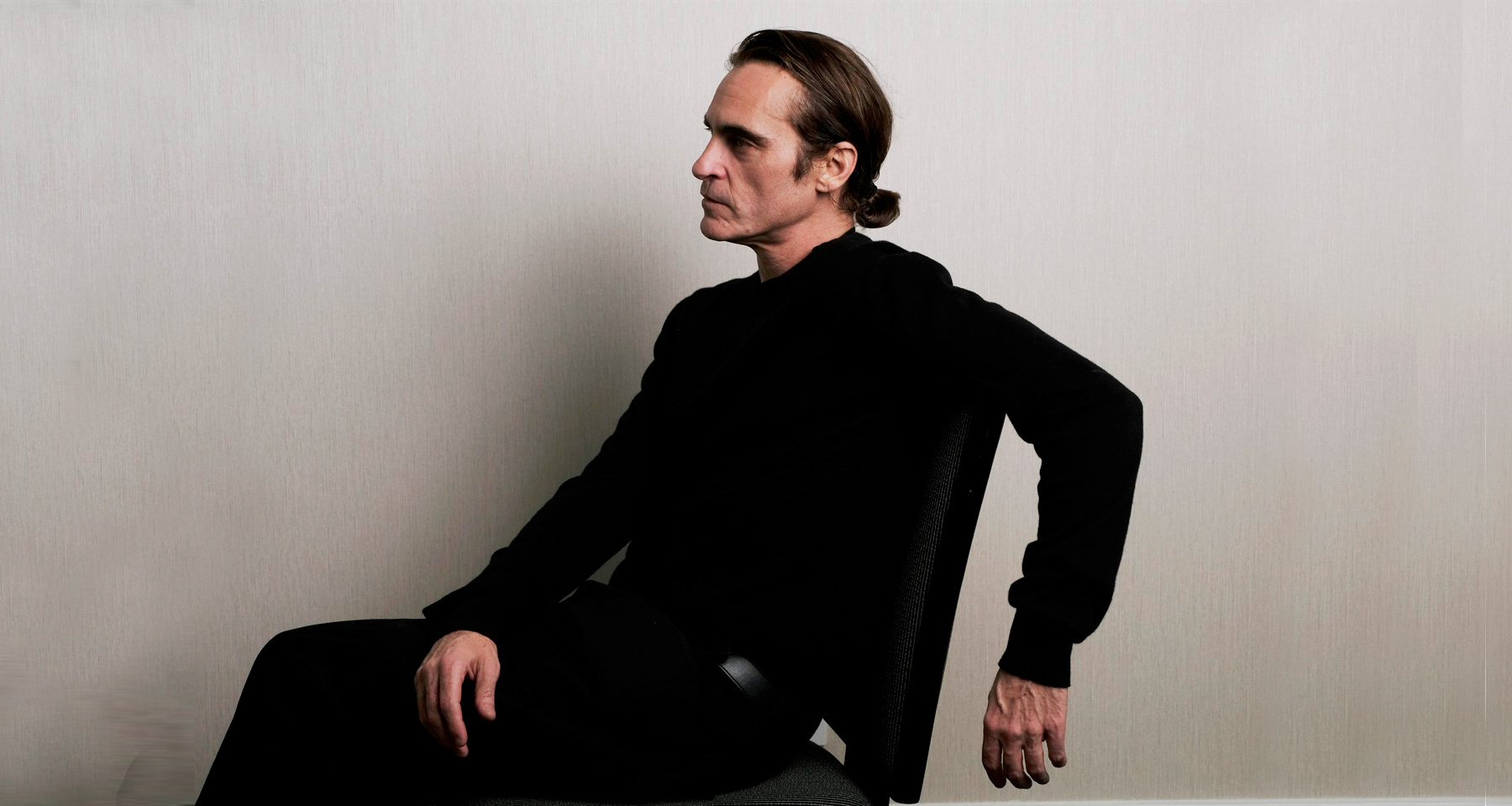

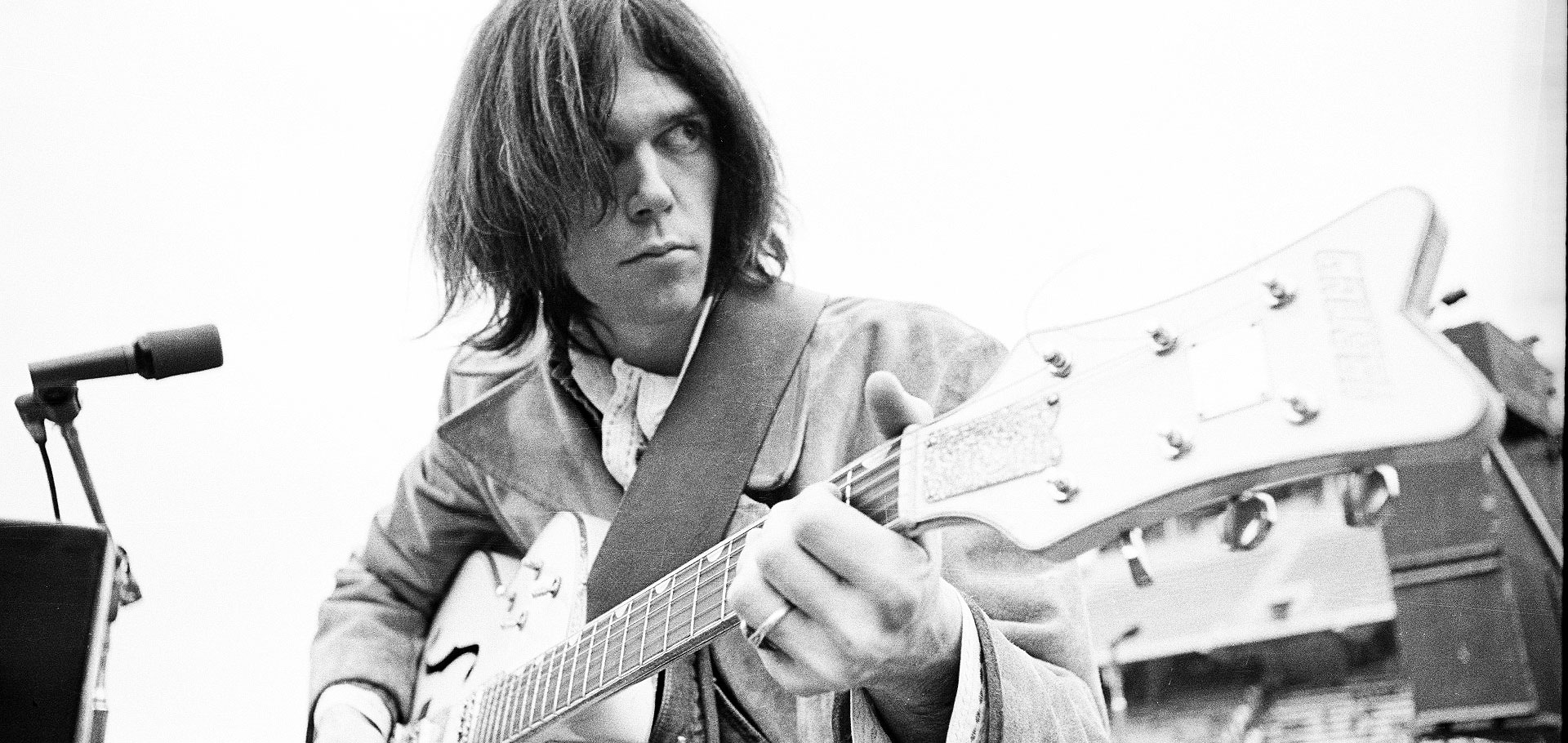

In 2017, I will pay attention to the long, strange wilderness journey of Neil Young. Few artists have had as long and varied career as the Canadian singer-songwriter, who sang in folk clubs in the 1960’s with Stephen Stills and Joni Mitchell, got the public’s attention with the band Buffalo Springfield, and began the 1970’s by joining Crosby, Stills, and Nash, adding darker tones and textures to the music of that remarkable group. That year also saw him release his breakthrough solo album, After the Gold Rush, which was one of the most formative albums in my life.

After that, Young’s career went on to follow a long, winding road with many detours, side trips, breakdowns, and refreshing oases, and it’s still going today. This complex journey makes it difficult for me to choose any single album as representative of what Neil Young has meant to me as an artist, poet, songwriter, and performer. Should I focus on After the Gold Rush, with its melancholy and sometimes mournful tones, Young’s plaintive, vulnerable vocals, its jagged, driving, angry social statements like “Southern Man,” and its simple, intimate tributes to romance? One review calls this album Young’s “requiem for the 60’s,” saying this:

But more than any of this, After the Gold Rush puts an end to ’60s idealism through a mix of songs that cut specifically — the meditative title track, a piano-driven ballad that ranks among Young’s very best — and more abstractly (the album’s opening cut, “Tell Me Why”) into the deep, overriding sorrow that runs throughout the record. “Look at Mother Nature on the run in the 1970s,” he sings on “After the Gold Rush,” pretty much sealing a fate nine months into the new decade.

Well, that’s fall all right — the end of idealism beside a flowing stream of sorrow. Mother Nature on the run.

But Young soon went on to even darker and deeper explorations into mortality. After his most successful commercial record, Harvest, his friend, former Crazy Horse guitarist Danny Whitten died of a drug overdose. And Young went from singing songs like the popular “Heart of Gold” to edgy, chaotic rock songs, such as those captured on the 1973 live album Time Fades Away. This, along with two other albums, Tonight’s the Night, and On The Beach, formed what came to be known as Neil Young’s “doom trilogy.”

Well, at this point we’re only in the mid-1970’s, folks, and since then Young has found more ways to reinvent himself and comment on life’s mixed bag than I have time to tell in one blog post. So many of his albums, then and in subsequent years, would be appropriate to consider during this season of mud and muck leading to rebirth. Therefore, instead of choosing one album on which to focus, I will take time this fall to explore the Neil Young catalogue, finding songs that speak to me of this journey, the incredible mix of romance and loss, fragility and strength, quiet whispers and overwhelming roars, and life and death that makes up fall.

Young has struck up musical collaborations throughout his career. From Buffalo Springfield, Crazy Horse, Crosby, Stills, & Nash have been his most renowned influences. But there are many interesting stories about Neil’s collaborations involving Bob Dylan, John Lennon, Pearl Jam, Lynyrd Skynyrd and Nirvana and influences on their music.

All these contrasts and more can be found in the music of Neil Young.

Hitchhiker

Reviewed by Tom Moon of NPR

Recording is a little bit like fishing. Sometimes you make elaborate preparations, get the best gear and set up in advantageous surroundings … only to wind up with zilch.

Sometimes you grab whatever is close at hand and just get busy. The hours go by like minutes, and the next thing you know, the bucket is full.

So it was for Neil Young on August 11, 1976, at Indigo Studios in Malibu.

The Canadian singer and songwriter had material he’d been developing, including three songs that became part of his landmark Rust Never Sleeps with Crazy Horse – “Pocahontas,” “Powderfinger” and “Ride My Llama.”

He showed up with acoustic guitar and harmonica (moving to piano for the final track, “The Old Country Waltz”), and after a shaky-voiced check-in with the control room – the first utterance is Young on the talkback microphone, asking longtime collaborator David Briggs “You ready, Briggs?” – he put down stark, blueprint-like solo renditions of songs that he’d develop into fervent anthems on later albums. There’s no affectation, no studio agony – just the songs, served straight up.

In this raw way, Hitchhiker is pre-history, offering tunes from Young’s extensive archive in just-past-sketchbook form. In his 2014 memoir, Special Deluxe, he recalls that he viewed the songs as a unified whole and recorded them that way, in rapid succession, “pausing only for weed, beer, or coke.” Then he sat on the results. Like other occasions throughout his career, he ultimately decided against releasing it. His explanation in the book: “I was pretty stony on it, and you can hear it in my performances.”

Still, Young knew the material was strong: Eight of the 10 tunes became part of his repertoire, albeit with significant alterations. “Powderfinger,” for one, mushroomed into something of an epic with Crazy Horse; here, it’s a crisp Deliverance-style tale of river life, delivered in underreachingly earnest phrases that capture the scattered anxieties of its 22-year-old narrator.

There are two never-before-released tracks – an underdeveloped ballad called “Hawaii” and a stunning traveler’s prayer, “Give Me Strength.” This one is a stone-cold stunner, with a beautiful Pete Seeger-ish chord sequence and lyrics that evoke the bittersweetness of the wandering life.

It’s not clear why Young chose to share Hitchhiker now, but the music itself might hold clues. “Campaigner,” which was on the 1977 Decade compilation, talks about political speech and duplicity, using almost pitying terms to speculate on the “soul” of Richard Nixon. Change the name and….voila, instant protest song!

Then there’s the line in “Human Highway” (which appeared on Comes A Time in 1978) that laments the coarseness that Young sensed was newly unleashed in American culture at the time: “Take my eyes from what they’ve seen / Take my head and change my mind / How could people get so unkind.”

The key word there is “get,” not “be.” Like many of Young’s couplets, this one voices, in harrowingly direct language, a slow-moving, tectonic shift that many feel but few articulate. It’s downright haunting, the way this moment from a productive night long ago resonates clear and true and apt, all over again.