you are of a certain age, you remember where you were when JFK was assassinated and Neil Armstrong made his moonwalk. To which it should be added, the first time you heard Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

The 50th anniversary of the U.S. release of the seminal Beatles album — considered by many rock music pundits to be the greatest rock album evah — was June 1, and there is little I can add that those pundits already have not said in their orgy of self reflection. Except that their treatment of Sgt. Pepper as some sort of heirloom like a Fabergé egg is misplaced because it is as whimsically fresh in 2017 as it was in 1967.

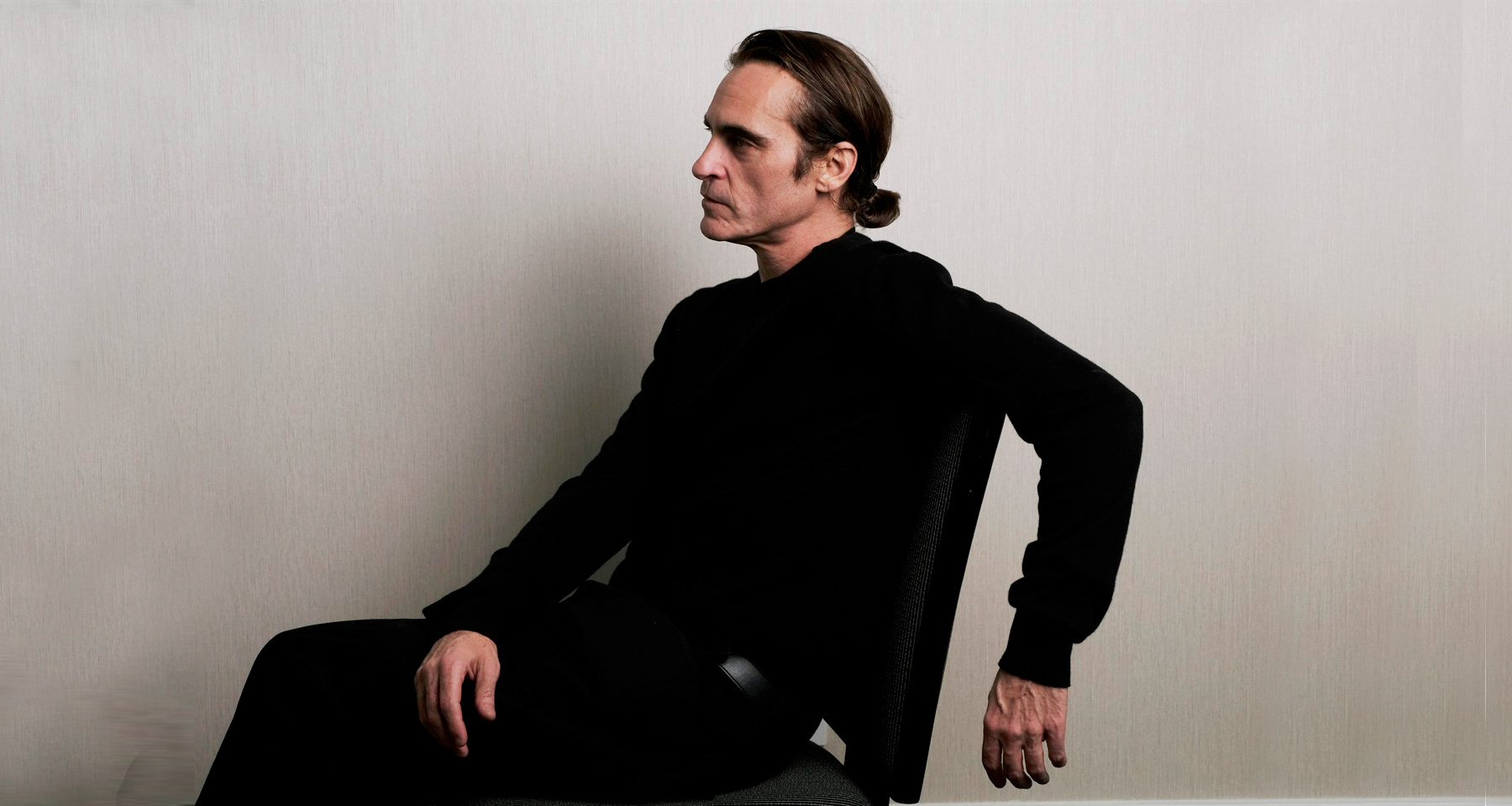

Then there’s the guy to the left of W.C. Fields on the Sgt. Pepper cover — Karlheinz Stockhausen (check them out in the image above). Do these critics think “Klavierstücke,” Stockhausen’s seminal piano work, is fusty just because its 65 years old? No, I didn’t think so.

Sgt. Pepper‘s release came amidst another earth-shaking event in my life — the Summer of Love — even though it was not yet technically summer and my first trip (mescaline, no less) was still a few weeks off, and my first trip to San Francisco a few weeks after that.

From the drum staccato at the opening of the first (and title) song of Sgt. Pepper to the sustained final piano note out of the orchestra crescendo at the end of “A Day In the Life,” the album was a smorgasbord of innovative instrumentation and breakthrough recording techniques, famously including reverse taping effects. Lest we forget, it was issued in mono. There have been numerous stereo remixes since, including the 50th anniversary $190 super duper deluxe box set remix by Giles Martin, son of original producer George Martin, that is said to be superb.

Then there was the album’s psychedelic aspect, which ignited my decades’ long interest in that genre of exotic music and art. Collecting, as well as ingesting.

So where was I the first time I heard Sgt. Pepper? By golly, I remember like it was yesterday. I bought the album on the morning it was released and looked forward to playing it when I got home after my shift as a police reporter for the local rag. But a nine-alarm factory fire kept me out until daybreak the next morning and I ended up playing it on the family room hi-fi at the home of the parents of my new romantic interest the following evening.

It wasn’t exactly make-out music. In fact, it was a huge distraction. But while my romantic interest faded by the end of the summer of the Summer of Love, my love of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band knows no season.

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was the first conceptual album in the history of Pop music. For the first time, a long play disc was conceived as a unitary work and, in addition, the symphony orchestra was used in it to enhance certain passages. The result today remains as a cornerstone of pop, a unique piece of a time when sound creation lived an unusual effervescence and where the hippy movement attracted the attention of half the world.

Sgt. Pepper’s is released on June 1, 1967 and appears almost as a tribute to some of the artists most admired by the Liverpool Quartet. In the great collage of the cover, you can see Karlheinz Stockhausen, just the fifth in the row above (counting from the left). It is known that the group sent Stockhausen a letter, through his representative, Brian Epstein, at the beginning of May of that year, requesting permission for his face to appear on the album cover. Not getting an answer from the German author, the Beatles insisted and, with urgency, they sent him a telegram. Stockhausen, who in those days was engaged in concerts by the United States and Europe, gave consent at last.

Paul McCartney’s admiration for the musician came from a few years ago, when he heard on the BBC The Singing of Teens (the electronic piece made in Cologne radio). The knowledge of the musics of the academic field by the members of the Beatles was not a unique case, because if something was distinguished that period of pop was due to the interrelation that existed between the different sound fields.

The influence of a composer like Varèse in the work of Frank Zappa is something that has transcended, but what perhaps is not known is the strong presence of musique concrète in many of the pieces that make up the first three (and brighter) albums The Mothers of Invention – Freak Out!, Absolutely Free and, above all, We’re Only in It for the Money (whose cover is a parody of Sgt Pepper’s ) contain passages that seem to have been made in Pierre Schaeffer’s own club d’essai . These concrete pieces are energized by the typical taste of the Mothers for the changes of record and by the critical look towards the American way of life.

The moments to retain of that experience of the band of Zappa are those that contribute an almost surrealist tone, already present in the same titles of the subjects:

- Invocation and Ritual Dance of the Young Pumpkin

- Retentive Nasal Calliope music

- The Return of the Son of Monster Magnet

The delirium that underlies this music extends to other works created by the bands that gathered in the San Francisco area. The Summer of Love, which in the strictly sound is known as psychedelia , left for the story a bouquet of pieces of enormous appeal, between traditional melodies and some electroacoustic work, which still amazes today, especially concentrating on such a period Brief time, from 1966 to 1968.

What made the Beatles different in that Summer of Love, with respect to their colleagues, was their universalist sense ( All you needs is love would eventually become an international anthem). The Beatles used electronic techniques, borrowing musicians like Stockhausen, to make pieces like Strawberry Fields Forever or I Am the Walrus sound objects that broke the barriers of the pop song.

Undoubtedly, it is the theme Revolution number nine , included in the “white album”, the one that most relates with the electronic experience. The band used up to a hundred fragments of popular hymns and dances thanks to the technique of collage .